Dropbox runs hundreds of services, written in different languages, which exchange millions of requests per second. At the core of our Service Oriented Architecture is Courier, our gRPC-based Remote Procedure Call (RPC) framework. While developing Courier, we learned a lot about extending gRPC, optimizing performance for scale, and providing a bridge from our legacy RPC system.

Note: this post shows code generation examples in Python and Go. We also support Rust and Java.

The road to gRPC

Courier is not Dropbox’s first RPC framework. Even before we started to break our Python monolith into services in earnest, we needed a solid foundation for inter-service communication. Especially since the choice of the RPC framework has profound reliability implications.

Previously, Dropbox experimented with multiple RPC frameworks. At first, we started with a custom protocol for manual serialization and de-serialization. Some services like our Scribe-based log pipeline used Apache Thrift. But our main RPC framework (legacy RPC) was an HTTP/1.1-based protocol with protobuf-encoded messages.

For our new framework, there were several choices. We could evolve the legacy RPC framework to incorporate Swagger (now OpenAPI). Or we could create a new standard. We also considered building on top of both Thrift and gRPC.

We settled on gRPC primarily because it allowed us to bring forward our existing protobufs. For our use cases, multiplexing HTTP/2 transport and bi-directional streaming were also attractive.

Note that if fbthrift had existed at the time, we may have taken a closer look at Thrift based solutions.

What Courier brings to gRPC

Courier is not a different RPC protocol—it’s just how Dropbox integrated gRPC with our existing infrastructure. For example, it needs to work with our specific versions of authentication, authorization, and service discovery. It also needs to integrate with our stats, event logging, and tracing tools. The result of all that work is what we call Courier.

While we support using Bandaid as a gRPC proxy for a few specific use cases, the majority of our services communicate with each other with no proxy, to minimize the effect of the RPC on serving latency.

We want to minimize the amount of boilerplate we write. Since Courier is our common framework for service development, it incorporates features which all services need. Most of these features are enabled by default, and can be controlled by command-line arguments. Some of them can also be toggled dynamically via a feature flag.

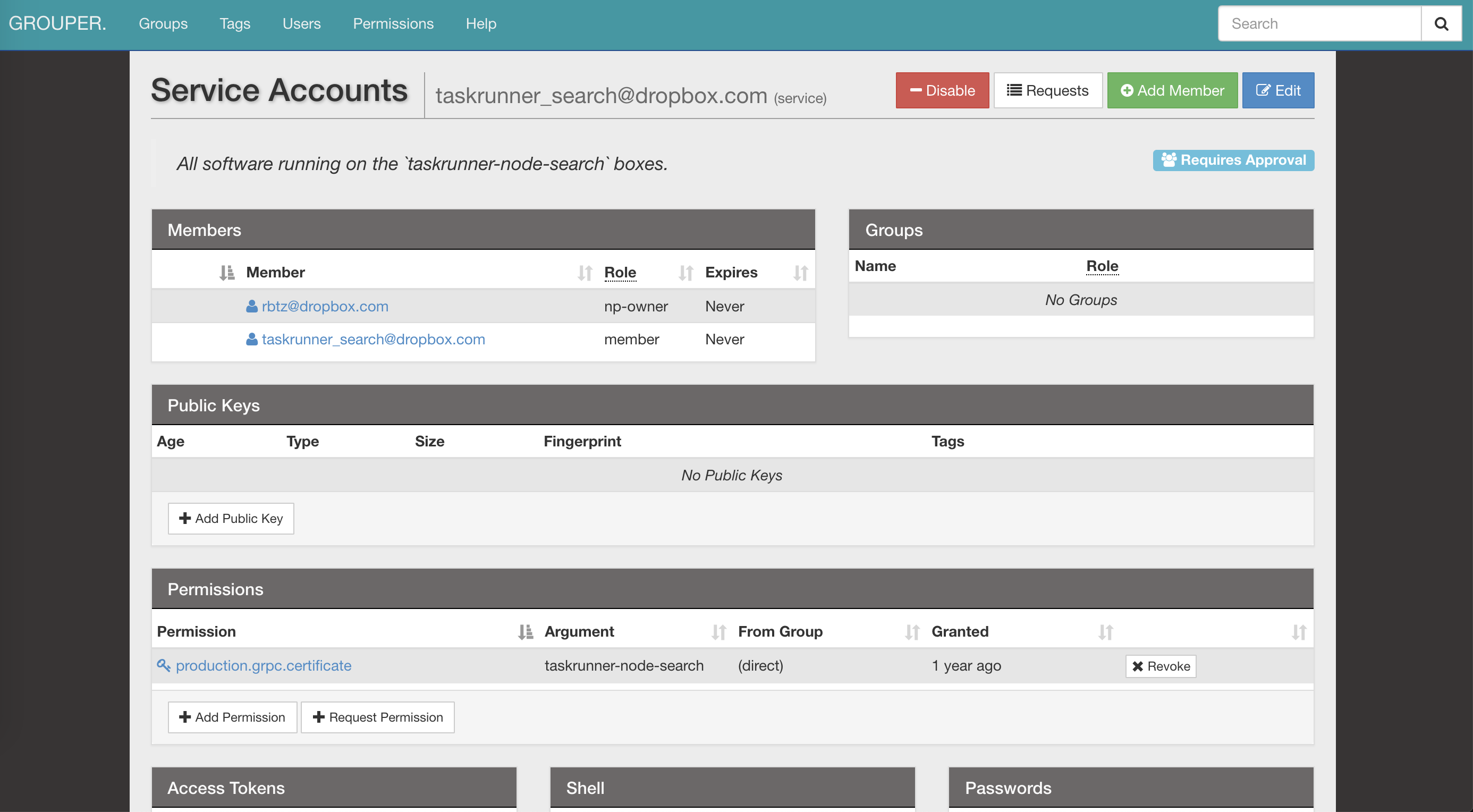

Security: service identity and TLS mutual authentication

Courier implements our standard service identity mechanism. All our servers and clients have their own TLS certificates, which are issued by our internal Certificate Authority. Each one has an identity, encoded in the certificate. This identity is then used for mutual authentication, where the server verifies the client, and the client verifies the server.

On the TLS side, where we control both ends of the communication, we enforce quite restrictive defaults. Encryption with PFS is mandatory for all internal RPCs. The TLS version is pinned to 1.2+. We also restrict symmetric/asymmetric algorithms to a secure subset, with ECDHE-ECDSA-AES128-GCM-SHA256 being preferred.

After identity is confirmed and the request is decrypted, the server verifies that the client has proper permissions. Access Control Lists (ACLs) and rate limits can be set on both services and individual methods. They can also be updated via our distributed config filesystem (AFS). This allows service owners to shed load in a matter of seconds, without needing to restart processes. Subscribing to notifications and handling configuration updates is taken care of by the Courier framework.

Service “Identity” is the global identifier for ACLs, rate limits, stats, and more. As a side bonus, it’s also cryptographically secure.

Here is an example of Courier ACL/ratelimit configuration definition from our Optical Character Recognition (OCR) service:

limits:

dropbox_engine_ocr:

# All RPC methods.

default:

max_concurrency: 32

queue_timeout_ms: 1000

rate_acls:

# OCR clients are unlimited.

ocr: -1

# Nobody else gets to talk to us.

authenticated: 0

unauthenticated: 0

We are considering adopting the SPIFFE Verifiable Identity Document (SVID), which is part of Secure Production Identity Framework for Everyone (SPIFFE). This would make our RPC framework compatible with various open source projects.

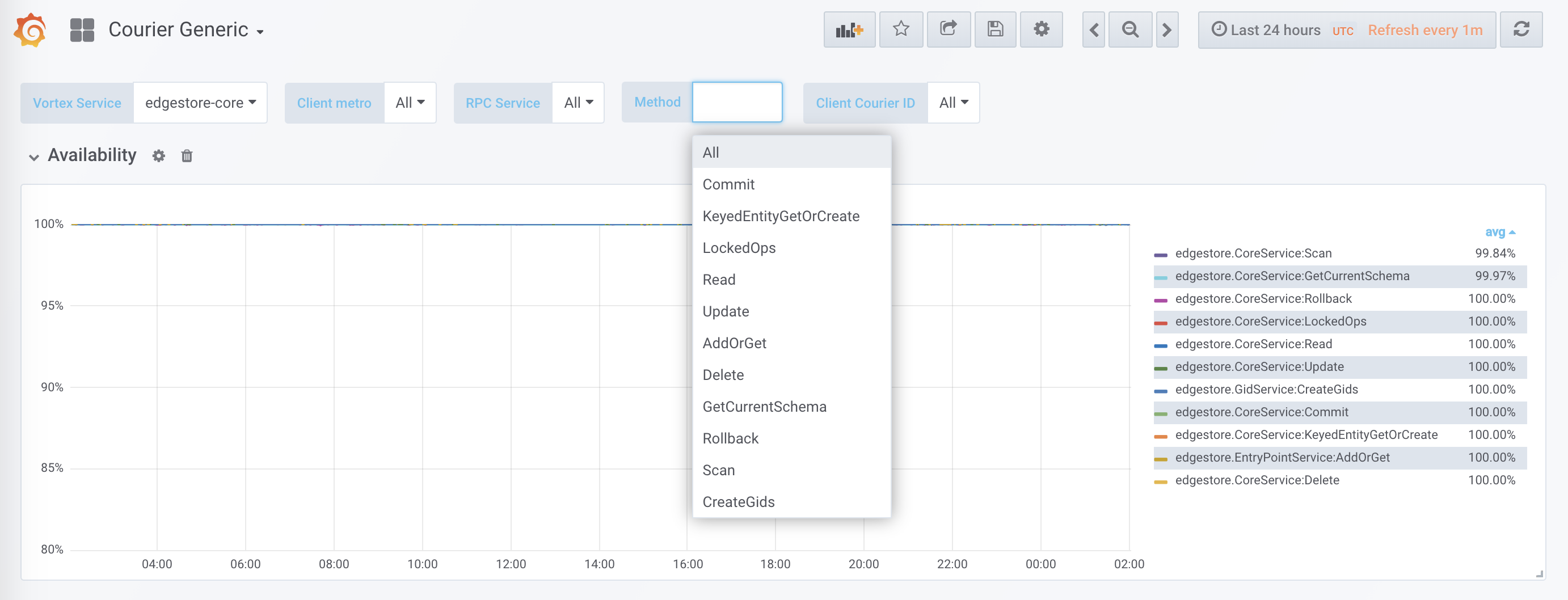

Observability: stats and tracing

Using just an identity, you can easily locate standard logs, stats, traces, and other useful information about a Courier service.

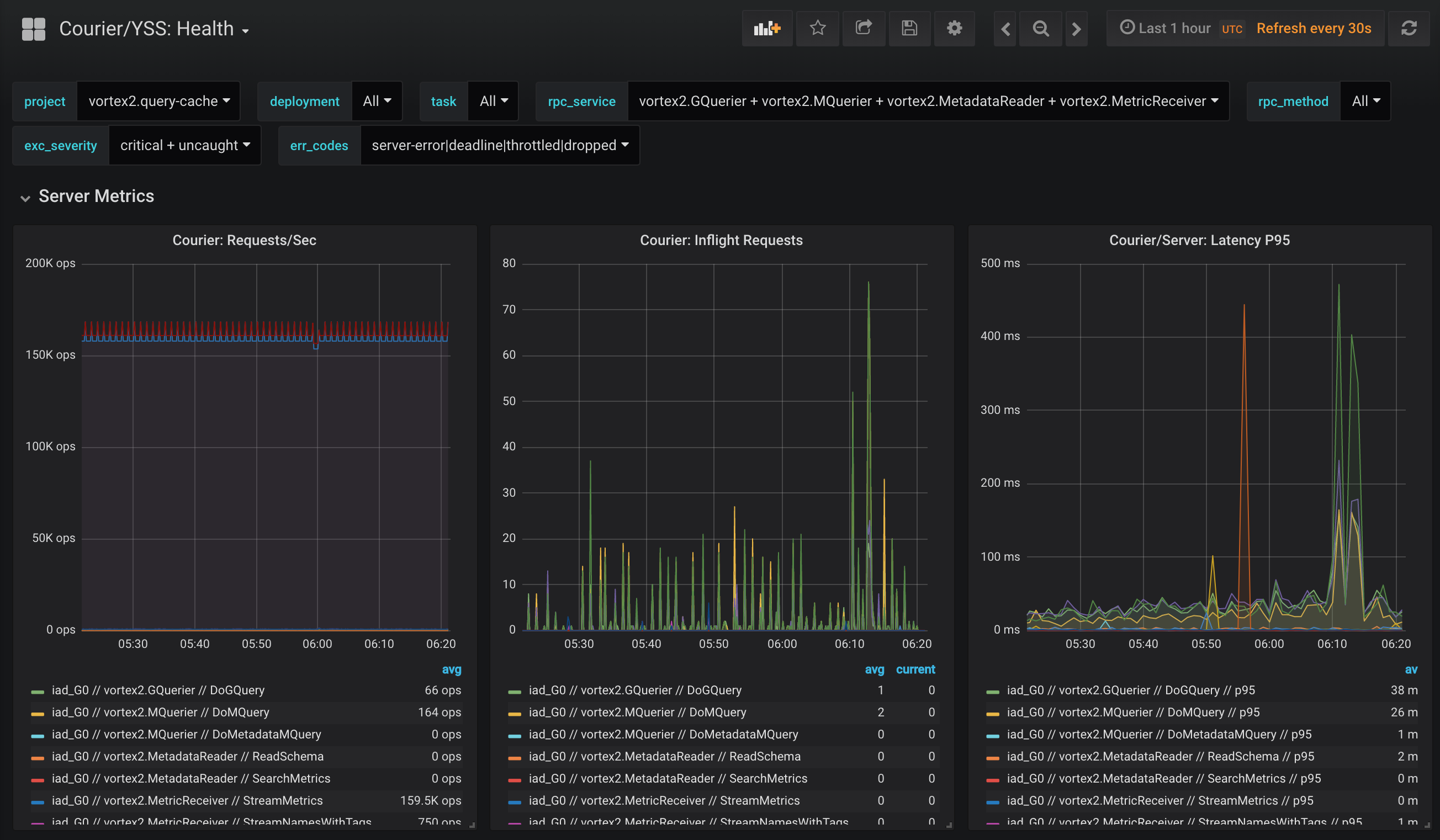

Courier stats include client-side availability and latency, as well as server-side request rates and queue sizes. We also have various break-downs like per-method latency histograms or per-client TLS handshakes.

One of the benefits of having our own code generation is that we can initialize these data structures statically, including histograms and tracing spans. This minimizes the performance impact.

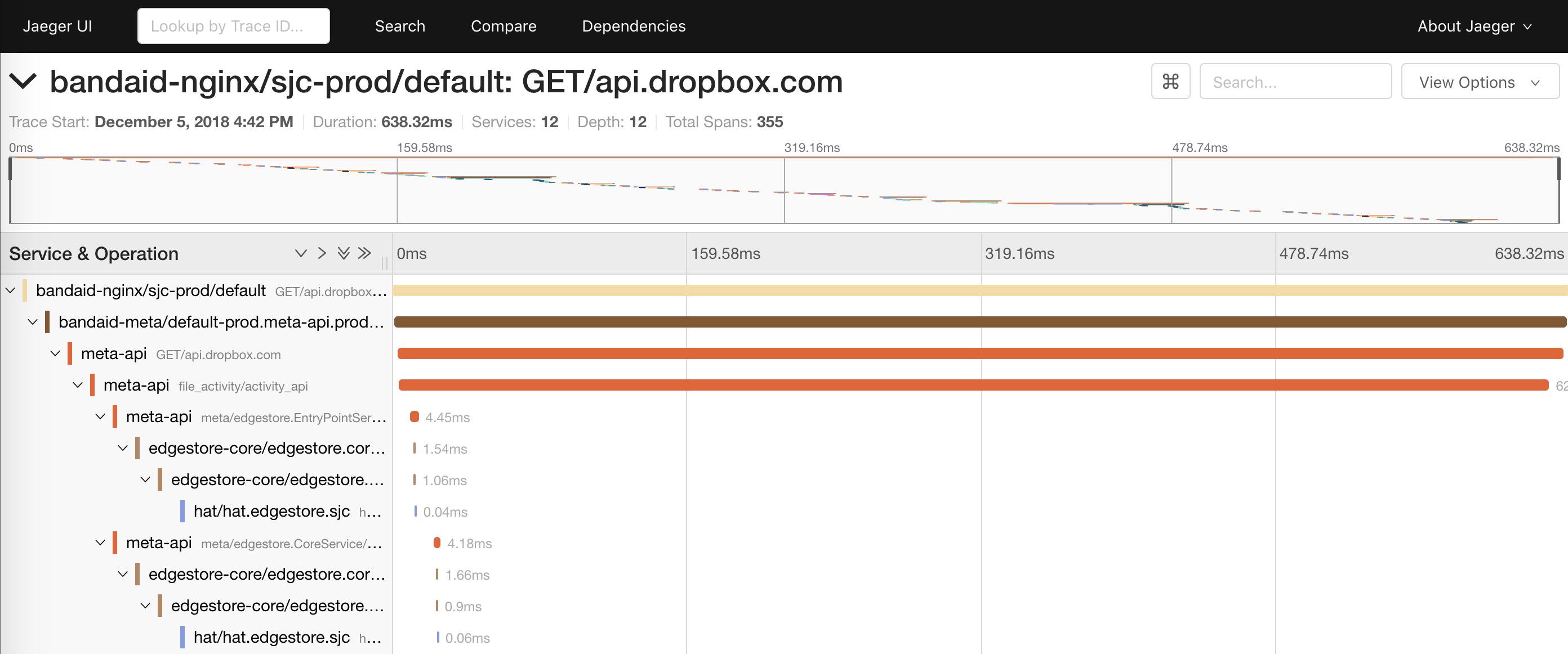

request_id across API boundaries. This allowed joining logs from different services. In Courier, we’ve introduced an API based on a subset of the OpenTracing specification. We wrote our own client libraries, while the server-side is built on top of Cassandra and Jaeger. The details of how we made this tracing system performant warrant a dedicated blog post.

Tracing also gives us the ability to generate a runtime service dependency graph. This helps engineers to understand all the transitive dependencies of a service. It can also potentially be used as a post-deploy check for avoiding unintentional dependencies.

Reliability: deadlines and circuit-breaking

Courier provides a centralized location for language specific implementations of functionality common to all clients, such as timeouts. Over time, we have added many capabilities at this layer, often as action items from postmortems.

Deadlines

Every gRPC request includes a deadline, indicating how long the client will wait for a reply. Since Courier stubs automatically propagate known metadata, the deadline travels with the request even across API boundaries. Within a process, deadlines are converted into a native representation. For example, in Go they are represented by a context.Context result from the WithDeadline method.

In practice, we have fixed whole classes of reliability problems by forcing engineers to define deadlines in their service definitions.

This context can travel even outside of the RPC layer! For example, our legacy MySQL ORM serializes the RPC context along with the deadline into a comment in the SQL query. Our SQLProxy can parse these comments and KILL queries when the deadline is exceeded. As a side benefit, we have per-request attribution when debugging database queries.

Circuit-breaking

Another common problem that our legacy RPC clients have to solve is implementing custom exponential backoff and jitter on retries. This is often necessary to prevent cascading overloads from one service to another.

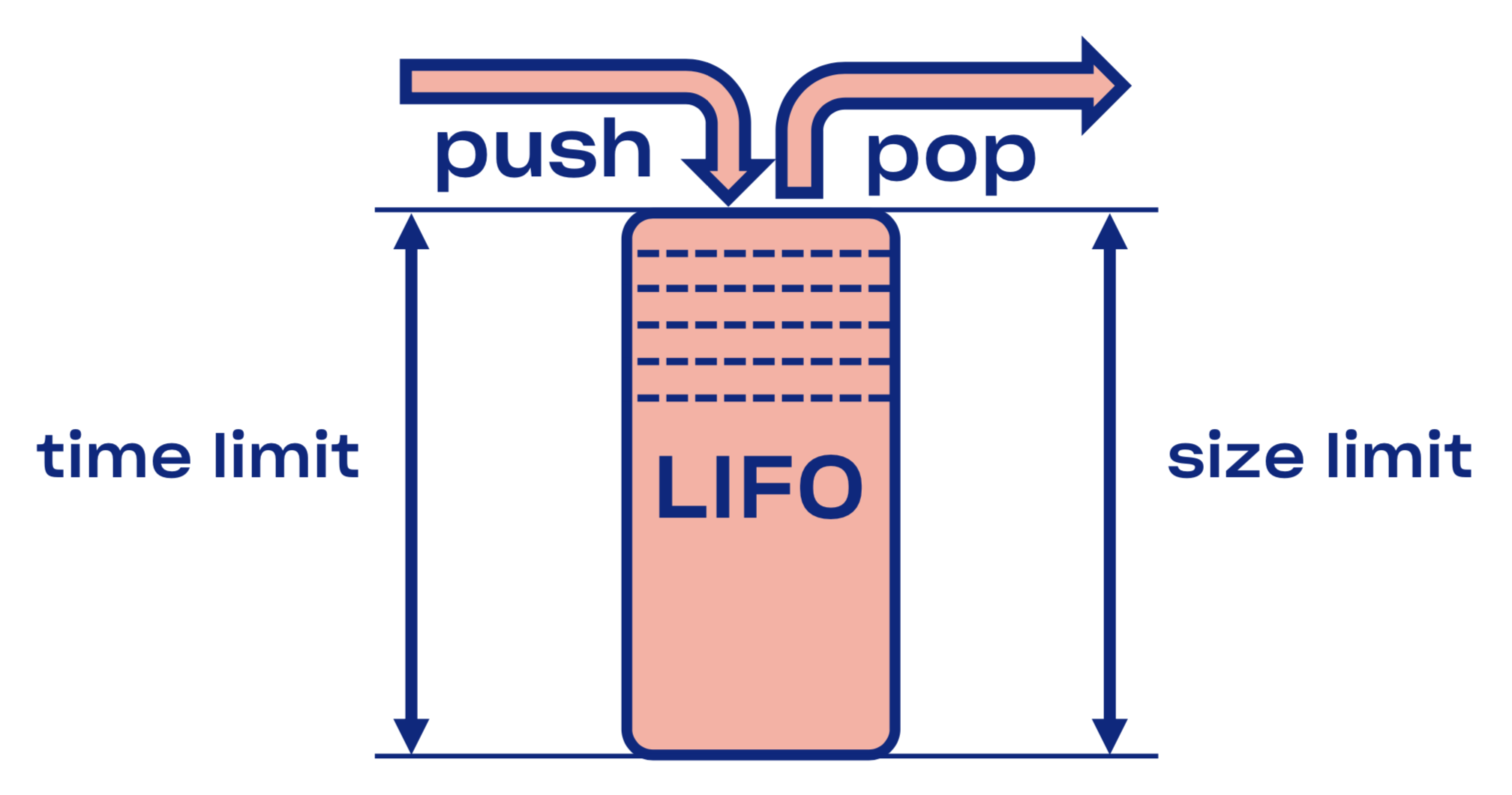

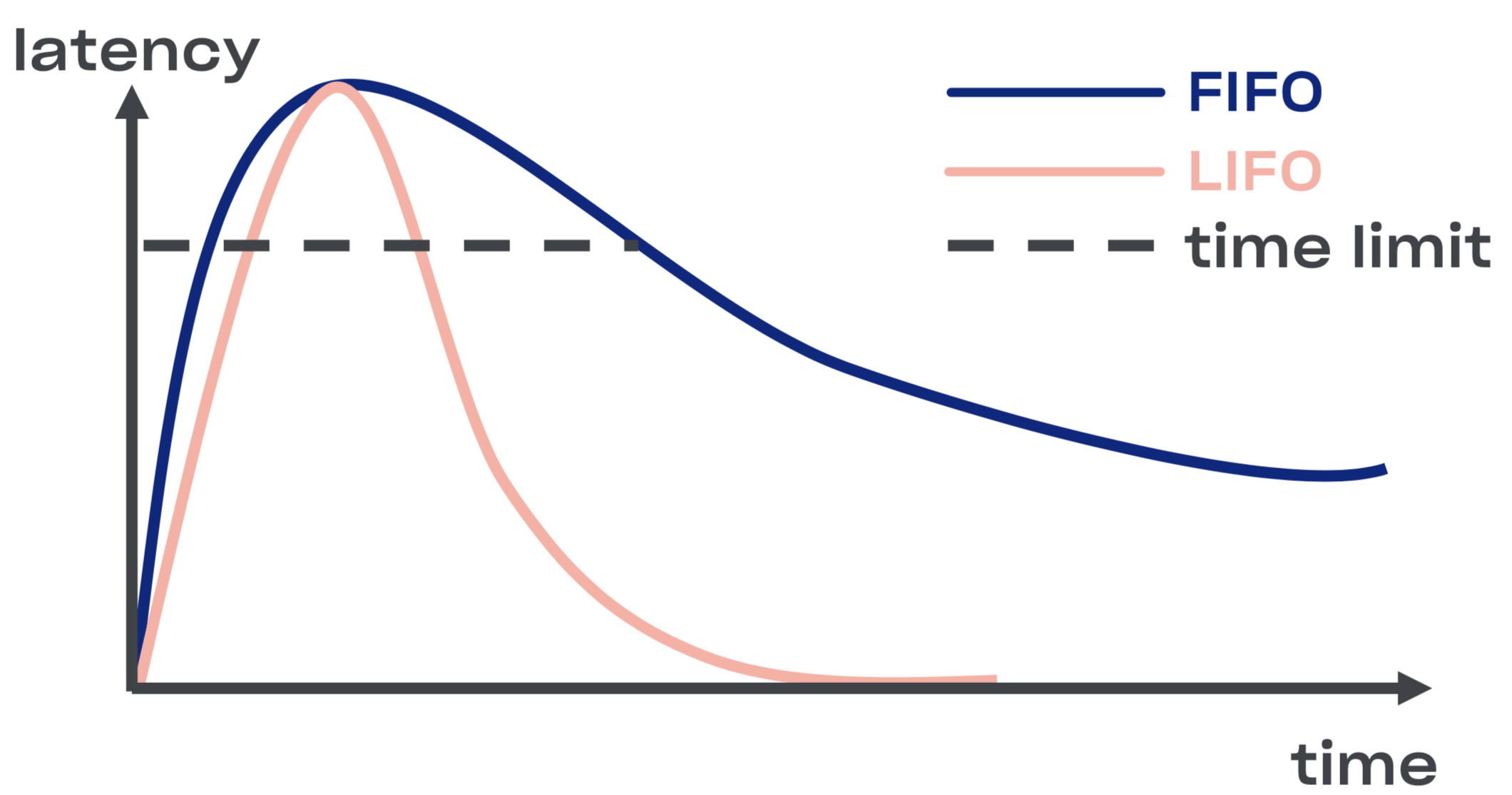

In Courier, we wanted to solve circuit-breaking in a more generic way. We started by introducing a LIFO queue between the listener and the workpool.

In the case of a service overload, this LIFO queue acts as an automatic circuit breaker. The queue is not only bounded by size, but critically, it’s also bounded by time. A request can only spend so long in the queue.

LIFO has the downside of request reordering. If you want to preserve ordering, you can use CoDel. It also has circuit breaking properties, but won’t mess with the order of requests.

Introspection: debug endpoints

Even though debug endpoints are not part of Courier itself, they are widely adopted across Dropbox. They are too useful to not mention! Here are a couple of examples of useful introspections.

For security reasons, you may want to expose these on a separate port (possibly only on a loopback interface) or even a Unix socket (so access can be additionally controlled with Unix file permissions.) You should also strongly consider using mutual TLS authentication there by asking developers to present their certs to access debug endpoints (esp. non-readonly ones.)

Runtime

Having the ability to get an insight into the runtime state is a very useful debug feature, e.g. heap and CPU profiles could be exposed as HTTP or gRPC endpoints.

We are planning on using this during the canary verification procedure to automate CPU/memory diffs between old and new code versions.

These debug endpoints can allow modification of runtime state, e.g. a golang-based service can allow dynamically setting the GCPercent.

Library

For a library author being able to automatically export some library-specific data as an RPC-endpoint may be quite useful. Good examples here is that malloc library can dump its internal stats. Another example is a read/write debug endpoint to change the logging level of a service on the fly.

RPC

It is given that troubleshooting encrypted and binary-encoded protocols will be a bit complicated, therefore putting in as much instrumentation as performance allows in the RPC layer itself is the right thing to do. One example of such an introspection API is a recent channelz proposal for the gRPC.

Application

Being able to view application-level parameters can also be useful. A good example is a generalized application info endpoint with build/source hash, command line, etc. This can be used by the orchestration system to verify the consistency of a service deployment.

Performance optimizations

We discovered a handful of Dropbox specific performance bottlenecks when rolling out gRPC at scale.

TLS handshake overhead

With a service that handles lots of connections, the cumulative CPU overhead of TLS handshakes can become non-negligible. This is especially true during mass service restarts.

We switched from RSA 2048 keypairs to ECDSA P-256 to get better performance for signing operations. Here are BoringSSL performance examples (note that RSA is still faster for signature verification):

RSA:

𝛌 ~/c0d3/boringssl bazel run -- //:bssl speed -filter 'RSA 2048'

Did ... RSA 2048 signing operations in .............. (1527.9 ops/sec)

Did ... RSA 2048 verify (same key) operations in .... (37066.4 ops/sec)

Did ... RSA 2048 verify (fresh key) operations in ... (25887.6 ops/sec)

𝛌 ~/c0d3/boringssl bazel run -- //:bssl speed -filter 'ECDSA P-256'

Did ... ECDSA P-256 signing operations in ... (40410.9 ops/sec)

Did ... ECDSA P-256 verify operations in .... (17037.5 ops/sec)

Since RSA 2048 verification is ~3x faster than ECDSA P-256 one, from a performance perspective, you may consider using RSA for your root/leaf certs. From a security perspective though it’s a bit more complicated since you’ll be chaining different security primitives and therefore resulting security properties will be the minimum of all of them. For the same performance reasons you should also think twice before using RSA 4096 (and higher) certs for your root/leaf certs.

We also found that TLS library choice (and compilation flags) matter a lot for both performance and security. For example, here is a comparison of MacOS X Mojave’s LibreSSL build vs homebrewed OpenSSL on the same hardware:

LibreSSL 2.6.4:

𝛌 ~ openssl speed rsa2048

LibreSSL 2.6.4

...

sign verify sign/s verify/s

rsa 2048 bits 0.032491s 0.001505s 30.8 664.3

𝛌 ~ openssl speed rsa2048

OpenSSL 1.1.1a 20 Nov 2018

...

sign verify sign/s verify/s

rsa 2048 bits 0.000992s 0.000029s 1208.0 34454.8

Encryption is not expensive

It is a common misconception that encryption is expensive. Symmetric encryption is actually blazingly fast on modern hardware. A desktop-grade processor is able to encrypt and authenticate data at 40Gbps rate on a single core:𝛌 ~/c0d3/boringssl bazel run -- //:bssl speed -filter 'AES'

Did ... AES-128-GCM (8192 bytes) seal operations in ... 4534.4 MB/s

memcpy operations was critical. In addition, we also made some of the changes to gRPC itself. Authenticated and encrypted protocols have caught many tricky hardware issues. For example, processor, DMA, and network data corruptions. Even if you are not using gRPC, using TLS for internal communication is always a good idea.

High Bandwidth-Delay product links

Dropbox has multiple data centers connected through a backbone network. Sometimes nodes from different regions need to communicate with each other over RPC, e.g. for the purposes of replication. When using TCP the kernel is responsible for limiting the amount of data inflight for a given connection (within the limits of/proc/sys/net/ipv4/tcp_{r,w}mem), though since gRPC is HTTP/2-based it also has its own flow control on top of TCP. The upper bound for the BDP is hardcoded in grpc-go to 16Mb, which can become a bottleneck for a single high BDP connection. Golang’s net.Server vs grpc.Server

In our Go code we initially supported both HTTP/1.1 and gRPC using the same net.Server. This was logical from the code maintenance perspective but had suboptimal performance. Splitting HTTP/1.1 and gRPC paths to be processed by separate servers and switching gRPC to grpc.Server greatly improved throughput and memory usage of our Courier services.golang/protobuf vs gogo/protobuf

Marshaling and unmarshaling can be expensive when you switch to gRPC. For our Go code, we’ve switched to gogo/protobuf which noticeably decreased CPU usage on our busiest Courier servers.As always, there are some caveats around using gogo/protobuf, but if you stick to a sane subset of functionality you should be fine.

Implementation details

Test service (the service we use in Courier’s integration tests). Service description

Let’s look at the snippet from theTest service definition:

service Test {

option (rpc_core.service_default_deadline_ms) = 1000;

rpc UnaryUnary(TestRequest) returns (TestResponse) {

option (rpc_core.method_default_deadline_ms) = 5000;

}

rpc UnaryStream(TestRequest) returns (stream TestResponse) {

option (rpc_core.method_no_deadline) = true;

}

...

}

option (rpc_core.service_default_deadline_ms) = 1000;

option (rpc_core.method_default_deadline_ms) = 5000;

option (rpc_core.method_no_deadline) = true;

The real service definition is also expected to have extensive API documentation, sometimes even along with usage examples.

Stub generation

Courier generates its own stubs instead of relying on interceptors (except for the Java case, where the interceptor API is powerful enough) mainly because it gives us more flexibility. Let’s compare our stubs to the default ones using Golang as an example.

This is what default gRPC server stubs look like:

func _Test_UnaryUnary_Handler(srv interface{}, ctx context.Context, dec func(interface{}) error, interceptor grpc.UnaryServerInterceptor) (interface{}, error) {

in := new(TestRequest)

if err := dec(in); err != nil {

return nil, err

}

if interceptor == nil {

return srv.(TestServer).UnaryUnary(ctx, in)

}

info := &grpc.UnaryServerInfo{

Server: srv,

FullMethod: "/test.Test/UnaryUnary",

}

handler := func(ctx context.Context, req interface{}) (interface{}, error) {

return srv.(TestServer).UnaryUnary(ctx, req.(*TestRequest))

}

return interceptor(ctx, in, info, handler)

}

Here, all the processing happens inline: decoding the protobuf, running interceptors, and calling the UnaryUnary handler itself.

Now let’s look at Courier stubs:

func _Test_UnaryUnary_dbxHandler(

srv interface{},

ctx context.Context,

dec func(interface{}) error,

interceptor grpc.UnaryServerInterceptor) (

interface{},

error) {

defer processor.PanicHandler()

impl := srv.(*dbxTestServerImpl)

metadata := impl.testUnaryUnaryMetadata

ctx = metadata.SetupContext(ctx)

clientId = client_info.ClientId(ctx)

stats := metadata.StatsMap.GetOrCreatePerClientStats(clientId)

stats.TotalCount.Inc()

req := &processor.UnaryUnaryRequest{

Srv: srv,

Ctx: ctx,

Dec: dec,

Interceptor: interceptor,

RpcStats: stats,

Metadata: metadata,

FullMethodPath: "/test.Test/UnaryUnary",

Req: &test.TestRequest{},

Handler: impl._UnaryUnary_internalHandler,

ClientId: clientId,

EnqueueTime: time.Now(),

}

metadata.WorkPool.Process(req).Wait()

return req.Resp, req.Err

}

That’s a lot of code, so let’s go over it line by line.

First, we defer the panic handler that is responsible for automatic error collection. This allows us to send all uncaught exceptions to centralized storage for later aggregation and reporting:

defer processor.PanicHandler()

One more reason for setting up a custom panic handler is to ensure that we abort application on panic. Default golang/net HTTP handler behavior is to ignore it and continue serving new requests (with potentially corrupted and inconsistent state).Then we propagate context by overriding its values from the metadata of the incoming request:

ctx = metadata.SetupContext(ctx)

clientId = client_info.ClientId(ctx)

stats := metadata.StatsMap.GetOrCreatePerClientStats(clientId)

This dynamically creates a per-client (i.e. per-TLS identity) stats in runtime. We also have per-method stats for each service and, since the stub generator has access to all the methods during the code generation time, we can statically pre-create these to avoid runtime overhead.Then we create the request structure, pass it to the work pool, and wait for the completion:

req := &processor.UnaryUnaryRequest{

Srv: srv,

Ctx: ctx,

Dec: dec,

Interceptor: interceptor,

RpcStats: stats,

Metadata: metadata,

...

}

metadata.WorkPool.Process(req).Wait()

Note that the golang gRPC library supports the Tap interface, which allows very early request interception. This provides infrastructure for building efficient rate-limiters with minimal overhead.

App-specific error codes

Our stub generator also allows developers to define app-specific error codes through custom options:enum ErrorCode {

option (rpc_core.rpc_error) = true;

UNKNOWN = 0;

NOT_FOUND = 1 [(rpc_core.grpc_code)="NOT_FOUND"];

ALREADY_EXISTS = 2 [(rpc_core.grpc_code)="ALREADY_EXISTS"];

...

STALE_READ = 7 [(rpc_core.grpc_code)="UNAVAILABLE"];

SHUTTING_DOWN = 8 [(rpc_core.grpc_code)="CANCELLED"];

}

Python-specific changes

Our Python stubs add an explicit context parameter to all Courier handlers, e.g.:from dropbox.context import Context

from dropbox.proto.test.service_pb2 import (

TestRequest,

TestResponse,

)

from typing_extensions import Protocol

class TestCourierClient(Protocol):

def UnaryUnary(

self,

ctx, # type: Context

request, # type: TestRequest

):

# type: (...) -> TestResponse

...

At first, it looked a bit strange, but after some time developers got used to the explicit ctx just as they got used to self.

Note that our stubs are also fully mypy-typed which pays off in full during large-scale refactoring. It also integrates nicely with some IDEs like PyCharm.

Continuing the static typing trend, we also add mypy annotations to protos themselves:

class TestMessage(Message):

field: int

def __init__(self,

field : Optional[int] = ...,

) -> None: ...

@staticmethod

def FromString(s: bytes) -> TestMessage: ...

These annotations prevent many common bugs, such as assigning None to a string field in Python.

This code is opensourced at dropbox/mypy-protobuf.

Migration process

Step 0: Freeze the legacy RPC

Before we did anything, we froze the legacy RPC feature set so it’s no longer a moving target. This also gave people an incentive to move to Courier, since all new features like tracing and streaming were only available to services using Courier.Step 1: A common interface for the legacy RPC and Courier

We started by defining a common interface for both legacy RPC and Courier. Our code generation was responsible for producing both versions of the stubs that satisfy this interface:type TestServer interface {

UnaryUnary(

ctx context.Context,

req *test.TestRequest) (

*test.TestResponse,

error)

...

}

Step 2: Migration to the new interface

Then we started switching each service to the new interface but continued using legacy RPC. This was often a huge diff touching all the methods in the service and its clients. Since this is the most error-prone step, we wanted to de-risk it as much as possible by changing one variable at a time.Low profile services with a small number of methods and spare error budget can do the migration in a single step and ignore this warning.

Step 3: Switch clients to use Courier RPC

As part of the Courier migration, we also started running both legacy and Courier servers in the same binary on different ports. Now changing the RPC implementation is a one-line diff to the client:class MyClient(object):

def __init__(self):

- self.client = LegacyRPCClient('myservice')

+ self.client = CourierRPCClient('myservice')

Step 4: Clean up

After all service clients have migrated it is time to prove that legacy RPC is not used anymore (this can be done statically by code inspection and at runtime looking at legacy server stats.) After this step is done developers can proceed to clean up and remove old code.Lessons learned

At the end of the day, what Courier brings to the table is a unified RPC framework that speeds up service development, simplifies operations, and improves Dropbox reliability.

Here are the main lessons we’ve learned during the Courier development and deployment:

- Observability is a feature. Having all the metrics and breakdowns out-of-the-box is invaluable during troubleshooting.

- Standardization and uniformity are important. They lower cognitive load, and simplify operations and code maintenance.

- Try to minimize the amount of boilerplate code developers need to write. Codegen is your friend here.

- Make migration as easy as possible. Migration will likely take way more time than the development itself. Also, migration is only finished after cleanup is performed.

- RPC framework can be a place to add infrastructure-wide reliability improvements, e.g. mandatory deadlines, overload protection, etc. Common reliability issues can be identified by aggregating incident reports on a quarterly basis.

Future Work

Courier, as well as gRPC itself, is a moving target so let’s wrap up with the Runtime team and Reliability teams’ roadmaps.

In relatively near future we wanted to add a proper resolver API to Python’s gRPC code, switch to C++ bindings in Python/Rust, and add full circuit breaking and fault injection support. Later next year we are planning on looking into ALTS and moving TLS handshake to a separate process (possibly even outside of the services’ container.)

We are hiring!

Acknowledgments

Contributors: Ashwin Amit, Can Berk Guder, Dave Zbarsky, Giang Nguyen, Mehrdad Afshari, Patrick Lee, Ross Delinger, Ruslan Nigmatullin, Russ Allbery, Santosh Ananthakrishnan.

We are also very grateful to the gRPC team for their support.